Indicators of change

Order 2222 revealed a gap between flexibility theory and planning and implementation practice – creating lessons that now resonate for data centers. These indicators track whether data center policies are bridging that gap or widening it.

|

Delayed RTO responses to new federal policies: FERC expected Order 2222 compliance to take 270 days: it will now take some RTOs a decade. We are watching for signs of drag in RTO responses to recent large load-related FERC / DOE orders.

|

||

|

Share of data centers seeking BTM co-location: The number of data center developers seeking connection behind-the-meter signals the degree of misalignment between the achievable grid connection speed and loads’ expectations.

|

||

|

Interconnection queue revision frequency: The number of times RTOs revise their load study procedures in a short period – indicating continued stakeholder dissatisfaction with connection processing (See: MISO ’24 / ’25 & ERCOT late ’25).

|

||

|

Abrupt tweaks to recently released plans: Changes to plans, policies, and programs after their official announcement – suggesting pace of evolving information and intensity of internal debates (See: SPP’s 2025 ITP transmission portfolio revision).

|

||

|

State-level proactive actions: As federal policymakers increasingly venture with comfort into the “gray area” of the federal / state energy policy mandate, watch for pre‑emptive policies released by state Commissions to retain control of the issue.

|

The promise of load flexibility: Haven’t we seen this before?

The recent context

Trump’s January 16, 2026 direction seeks to address PJM’s capacity shortage. The policy response reflects sophisticated thinking about cost allocation and investment certainty. By requiring data centers to shoulder responsibility for new generation buildout through long-term contracts, it addresses legitimate concerns about free-riding and cost-shifting to existing ratepayers. The policy response reflects sophisticated thinking about cost allocation and investment certainty, yet the policy debate has limited consideration of recent precedent.

Order 2222: The original flexibility shortcut

The industry has confronted this exact challenge recently. FERC Order 2222, issued in September 2020, promised to revolutionize wholesale markets by enabling distributed energy resources (DERs) to participate alongside traditional generation. RTOs filed compliant tariffs, investors funded DER aggregation platforms, and the paradigm shift appeared inevitable.

FERC Order 2222: Limited results after five years

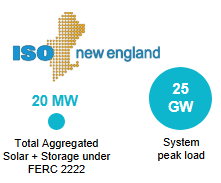

Since inception, FERC Order 2222 resources (solar + storage) account for 0.08% of total system peak load.

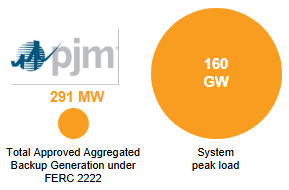

Since inception, FERC Order 2222 resources (solar + storage) account for less than 0.2% of total system peak load.

Lessons for data center planning

This is not about regulatory failure or utility obstruction. Every RTO made significant efforts to comply in time and many barriers came down. What did not materialize at expected scale was participation because the order did not fully resolve the fundamental tension between operational flexibility and planning certainty that continues to be the price of entry for dispatch.

That same tension now governs the data center debate. The scale has changed from kilowatts to hundreds of megawatts, but the underlying question is identical: can planning systems built for reliability accept operational flexibility as a substitute for firm capacity? Order 2222’s limited participation and extended timelines indicate challenges in this approach, providing a direct roadmap for current large load policy discussions.

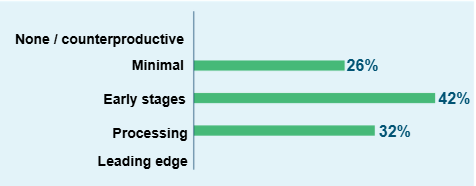

Our survey reinforces that a variety of different flexible and distributed solutions are being explored, but may still be in the early innings

DERs are increasingly viewed as a potential resilience asset. How would you characterize the industry’s current ability to integrate DERs effectively as part of the resilience toolkit?

Breakdown of survey responses

– None / counterproductive – Current frameworks may actually hinder DER participation during resilience.

– Minimal – DER integration remains fragmented and largely outside formal resilience planning.

– Early stage – The industry is still experimenting; DERs are not yet systematically incorporated into resilience strategies.

– Progressing – Pilot programs and selective deployments show promise, but scalability and coordination remain limited.

– Leading edge – DERs are being actively integrated into resilience and reliability planning, supported by strong regulatory and operational frameworks.

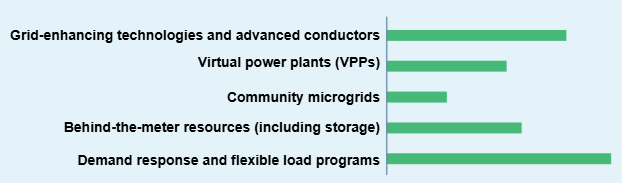

Utilities are exploring a range of distributed and flexible resource strategies to enhance reliability, resilience, and system efficiency. Which of the following approaches is your organization actively pursuing? Select all that apply

Breakdown of survey responses

– Grid-enhancing technologies and advanced conductors – Expanding transfer capability and system visibility without major rebuilds.

– Virtual power plants (VPPs) – Aggregating distributed assets to provide grid services at scale.

– Community microgrids – Developing localized resilience and flexibility solutions serving critical loads or communities.

– Behind-the-meter resources (including storage) – Integrating customer-sited generation, storage, and control systems.

– Demand response and flexible load programs – Leveraging customer or industrial flexibility to manage peak demand and grid stress.

The promise that wasn’t: A FERC order sprint turned to a saga

When FERC issued Order 2222 on September 17, 2020, it directed RTOs and ISOs to revise their tariffs to allow aggregated DERs like batteries, rooftop solar, and smart thermostats to participate directly in wholesale capacity, energy, and ancillary services markets. The order removed formal barriers that had prevented small, customer-sited resources from competing alongside traditional generation. All that was left to do, it seemed, was for ISOs and RTOs to implement it.

FERC set a 270-day compliance deadline. Industry press called the order a “game changer.” Investor presentations projected DER aggregators as nimble technology platforms poised to leap over the complexity and conservatism of traditional utility planning. Share prices for publicly traded aggregators like Sunrun and Generac peaked around this period – though admittedly they were also buoyed by complementary tailwinds of low interest rates and generous Inflation Reduction Act subsidy announcements. Competitively priced “flexibility at scale” seemed like an inevitability.

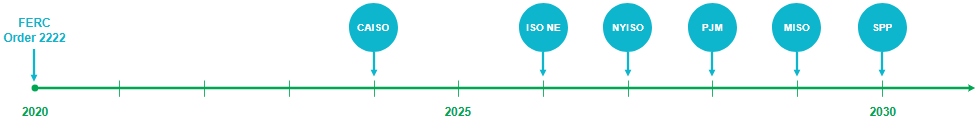

The implementation timeline tells a different story. As of January 2026, only two of the six RTOs are within the striking distance of implementation: California ISO completed its implementation as of November of 2024, and ISO New England appears on track for late 2026. New York ISO expects full implementation by end of 2026. PJM will not achieve energy market participation until February 2028, with capacity market access delayed until the 2028/2029 delivery year. MISO is working toward two-phase implementation ending in June 2029. SPP’s proposed implementation date is second quarter of 2030 – nearly a full decade after the order was issued.

FERC Order 2222 Latest Implementation Timeline by RTOs

Latest full compliance timeline estimates

DERs & VPPs footprint grew, but not where FERC hoped it would

The wholesale market participation of aggregated DERs that has materialized is modest – to the point of invisibility against system scale. PJM approved approximately 290 MW of aggregated backup generation in its 2023 capacity auction – a figure that is vanishingly small against PJM’s system peak of over 160 GW. Critically, this capacity represents a resource type that market operators already understand: dispatchable backup generation with firm fuel supply and discrete operating obligations. It fits much more naturally into the existing resource accreditation frameworks in ways that probabilistic flexibility does not.

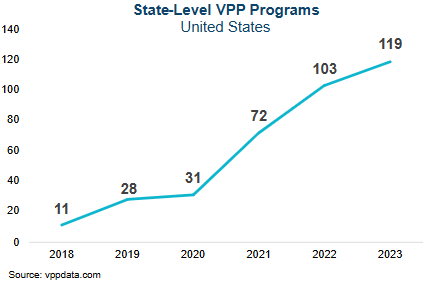

Meanwhile, at the state level, DER programs have proliferated to a greater degree. Since 2019 the number of VPP and DER aggregation programs grew from fewer than a dozen pilots across FERC-regulated markets to more than 100 active programs. Many remain quite small, but the activity level has been far more vibrant. While some publications report higher numbers of VPP instances, the difference appears to relate to counting methodologies (e.g. counting one program offered by two aggregators as two VPPs).

The VPP growth masks a critical detail: the vast majority operate under state regulatory jurisdiction, not wholesale market integration. In PJM, for example, commercial and industrial demand response aggregators have long been active, with thousands of sites providing approximately 7 GW in PJM’s capacity market, but these are legacy programs that predate Order 2222, operating under established measurement and verification protocols.

Even large increases in energy storage participation—such as ISO New England’s procurement of over 1,800 MW in FCA 18—were driven by state clean energy mandates, utility solicitations, and Order 841 reforms, not Order 2222 aggregation.

Inspired by state actions & outdone by them

FERC Order 2222 was modelled after California’s Distributed Energy Resource Provider (DERP) model that allowed participation of aggregated DERs in the one-state wholesale market as early as 2017. Since the FERC order’s release, the bulk of the VPP program growth occurred under the auspices of state regulator-authorized programs that primarily target more local grid benefits.

Wholesale market participation of DERs remains limited

The pattern holds across markets:

CAISO currently lists fewer than ten registered DER aggregators with market-based rate authority, despite being frequently cited as the “success case” for Order 2222 implementation – and the inspiration for the original order given California’s earlier start in the DER aggregation space. NYISO shows only a handful of DER providers eligible for wholesale transactions, despite representing the jurisdiction with a robust state-level DER program landscape.

In MISO and SPP, no comparable volumes of new DER aggregation have materialized despite extensive compliance work on the parts of the market administrators.

Even ISO New England’s frequently cited 20 MW of aggregated residential solar-plus-storage that cleared in 2019 – the first time such resources participated in any capacity market relied on solar installations that state policies had enabled to exist over the preceding decade, according to the winning bidder Sunrun. While groundbreaking, this success came from a single aggregator with strong utility partnerships, deploying resources at pilot scale with measurement and verification requirements far easier to establish and maintain than mass market adoption would require.

So, what went wrong? Nothing, if you believe the market administrators acted rationally.

Why compliance is not the same as participation

The central lesson from FERC Order 2222 is straightforward but critical:

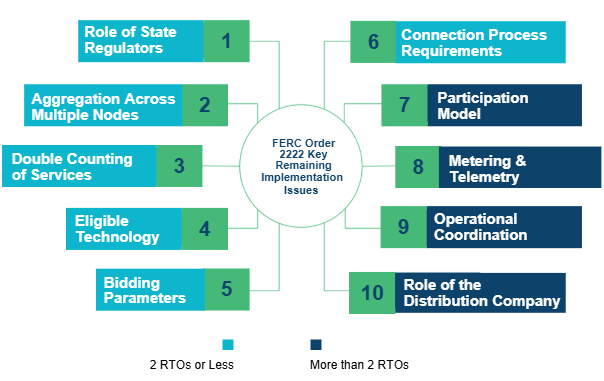

Regulatory compliance does not guarantee market participation at scale. Every RTO ultimately filed tariffs, often after multiple iterations and extended negotiations with FERC. ISO New England alone submitted eight compliance filings before receiving conditional approval, with implementation still ongoing. PJM filed its initial compliance plan in early 2022, received a deficiency letter in 2023, and did not finalize revisions until later that year. MISO’s proposed implementation timeline was rejected as too slow, then reapproved with a schedule extending into 2029. While formal barriers were removed, actual entry into wholesale markets remained limited because the order did not resolve the planning and operational constraints that determine whether a resource can be relied upon for system reliability.

Planning requirements create practical barriers

To count as capacity, planners must assume a resource will perform under stress conditions, verify that performance, and defend those assumptions to regulators and ratepayers. Order 2222 enabled aggregation, but it preserved three fundamental realities. First, distribution utilities retain physical and jurisdictional control over customer-sited resources and may override wholesale dispatch for safety or reliability reasons. This is not obstruction; it reflects legal authority and operational necessity. Second, verification standards favor hard telemetry over probabilistic inference. Statistical baselines and portfolio diversity appear attractive in theory but tend to fail when customer behavior changes during extreme system conditions—the very moments when capacity is most valuable. As a result, ISOs imposed telemetry, metering, and coordination requirements that limited eligible participation to resources with proven infrastructure. Third, cost recovery for enabling infrastructure—such as DERMS, advanced metering, protection upgrades, and feeder enhancements—remained uncertain. Absent regulatory clarity on who pays and how, utilities rationally slowed investment.

Market operators adapted to prioritize reliability

Faced with these constraints, ISOs modified their tariffs to reduce operational risk. They preserved or expanded utility veto points, required granular telemetry, restricted aggregation to specific nodes, or imposed minimum size thresholds that effectively excluded residential resources. Each change improved planning defensibility but reduced participation. This outcome is not paradoxical; it is the predictable result of asking institutions designed around centralized generation to internalize resources whose availability and control sit partly outside their authority. Comfort levels ultimately reflected the degree of control and accountability planners were willing to assume.

Order 2222 lessons for large-load planning

What the experience revealed

Market reforms relying on operational flexibility succeed only when institutions can translate flexibility into defensible planning assumptions. Where translation fails, progress stalls. Order 2222 under-delivered not because aggregation was flawed, but because it exposed how much infrastructure is required before flexibility can be relied upon for reliability.

The experience revealed conditions under which flexibility becomes operational: hard telemetry, enforceable obligations, jurisdictional clarity, and cost certainty. These require years of system upgrades and regulatory coordination. Order 2222’s 270-day compliance clock became five-to-ten-year timelines because planning institutions cannot assume performance without proof.

Large-load interconnection faces the same constraint with higher stakes. Speed will not come from voluntary curtailment commitments or self-sufficiency claims. It will come from mechanisms planners can model and regulators can defend.

Requirements for progress

First, service definitions must be precise enough to be modeled. Vague “flexibility” commitments are unusable in reliability planning. Only binding, verifiable service levels— maximum grid draw under contingencies, guaranteed curtailment response times, financial penalties for non-performance—can be incorporated into planning models. SPP’s High Impact Large Load programs illustrate this by defining exposure rather than assuming flexibility. FERC’s December 2025 directive for PJM to develop transmission service types reflects the same logic, but defining those services will require extended stakeholder processes.

Second, cost allocation must align with state regulatory authority. Transmission and enablement infrastructure require state commission approval for cost recovery. Federal acceleration that bypasses this produces delay and litigation, not infrastructure. The thirteen governors’ endorsement signals meaningful political support for assigning costs to data centers. Translating that support into approved rate structures, however, requires commission proceedings in multiple jurisdictions on timelines measured in years.

Third, planners must assume flexibility fails under stress unless proven otherwise. Reliability standards are built around worst-case outcomes, not average behavior. The one-in-ten-year planning criterion cannot be satisfied by probabilistic resources unless they demonstrate performance under stress conditions. Order 2222 aggregators encountered this through repeated FERC deficiency letters demanding tighter definitions and stronger verification. Large-load developers will likely face the same requirements. This is not resistance to innovation; it is the price of making innovation durable where failure carries catastrophic consequences.

Now what?

The January 16, 2026 announcement from the Trump administration and PJM state governors represents a serious attempt to address real shortcomings in capacity procurement and cost allocation. It correctly rejects the notion that data centers can free-ride on existing capacity and recognizes that long-term contracts may provide investment certainty that annual auctions do not.

Implementation reality

What it does not change is the pace of implementation. Procurement mechanisms can be accelerated, but auctions can be held on compressed timelines only if auctions are not implementation.

Implementation requires:

– Transmission upgrades requiring state approval and billions in investment

– Interconnection queues with tens of gigawatts in signed agreements awaiting commercial operation

– Coordination among transmission operators, distribution utilities, generators, regulators, and commissions operating under different authorities

The flexibility fallacy

The flexibility fallacy is appealing because it sounds modern and efficient. But flexibility that cannot be verified, enforced, or translated into conservative planning assumptions is not a resource – it is a risk. Planning institutions move at the speed of verification, not aspiration. That speed is slow, but it is how reliability is preserved.

Historical context

Order 2222 took 270 days on paper and many years in practice. The gap between procurement and performance for large-load policy will be similar, and likely wider given the scale and complexity involved.

“To what extent do you believe utilities will need to fundamentally transform their business models to respond effectively to data center growth?”

Over 50% of survey respondents agree that significant adaptation is needed, including a rethink on infrastructure planning, regulatory engagement, and service offerings, while the remainder is evenly split between moderate adjustments or major transformational (evolve toward a more commercial, customer-centric model

Authors: Dmitry Balashov, Margarita Patria

Our thanks to Charles Zhou for research support.